Gradient Descent explained

Introduction

First of all let’s define what is an optimization problem. An optimization task refers to minimize or maximize a given function $f(x)$ by modifying $x$.

The function $f(x)$ is also called objective function, criterion, or also loss function, cost function.

Given a loss function $f(x)$, we can denote its slope at $x$ with $\frac {d y} {d x}$ or equivalently $f’(x)$ (its derivative). As we know the derivative tells us how much the function increases when we increase by a small step $\eta$ called learning rate. So if we want to minimize the loss function we have to move $x$ in the opposite direction described by the gradient of the loss function w.r.t $x$. This is the basic idea behind the gradient descent algorithm.

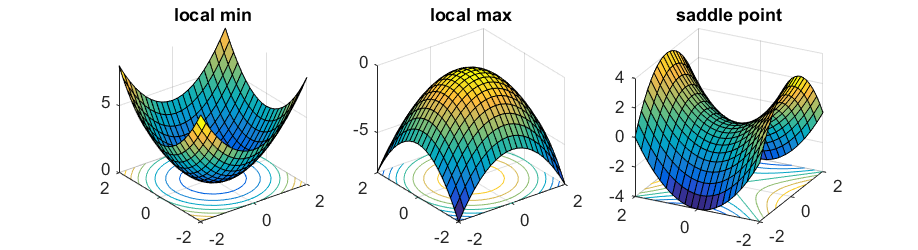

But how do we search this minimum? If $f’(x) = 0$ the derivative gives no information about the direction to go, so it should be reasonable to consider it the minimum.

The $x$ where $x = \text{arg} \ f’(x) = 0$ and $x = \text{arg min} f(x)$ is called global minimum.

Whenever the derivative $f’(x)$ is nonzero, as long as we choose a small enough step, the algorithm is guaranteed to make local progress. When the gradient is equal to $0$, the point is called a critical point, and the gradient descent algorithm will get stuck. For (strongly) convex functions, there is a unique critical point which is also the global minimum.

To distinguish these cases we need to consider the second order derivative $f’’(x)$, in particular we have to analyze the relative Hessian matrix.

To distinguish these cases we need to consider the second order derivative $f’’(x)$, in particular we have to analyze the relative Hessian matrix.

The gradient descent algorithm iteratively exploits the derivative of the loss function to compute the next point as follows:

$$

\begin{equation}

x’ = x - \eta \nabla_x f(x)

\label{eq:basic_GD}

\end{equation}

$$

In the machine learning literature, we often use the notation $J(\theta)$ or $\mathcal L(\theta)$ to denote the $f(x)$ loss function, where $\theta$ represents the parameters of the model that we want to optimize.

The following code snippet shows an example of how the gradient descent algorithm might be implemented:

1 | for i in range(n_epochs): |

Okay, now you might ask how we can efficiently compute the gradient for each parameter, since the number of trainable parameters for some of the most used language models like BERT have millions of parameters to optimize, and even bigger models like GPT-3 have billions of parameters!.

To answer this question, we use a technique called backward mode differentiation (I will probably explain this in the next post of this machine learning series), the basic idea is to use the chain rule to compute the gradients with efficient matrix product multiplication.

SGD

To overcome the gradient computation problem for large datasets we could compute the gradient for each sample of the dataset. This method is also called Stochastic Gradient Descent.

We modify the update equation as follows:

$$\theta = \theta - \eta \cdot \nabla_\theta J( \theta; x^{(i)}; y^{(i)})$$

where $x^{(i)}$ and $y^{(i)}$ are the feature sample and the label, respectively.

The optimization routine can also be modified as shown is the following snippet:

1 | for i in range(nb_epochs): |

Mini-Batch GD

This method takes the best of both worlds by computing the gradients for each batch of the dataset containing $n$ samples. We can formalize the updating rule, taking into account the dataset’s batch as follows:

$$\theta = \theta - \eta \cdot \nabla_\theta J( \theta; x^{(i:i+n)}; y^{(i:i+n)})$$

The optimization routine can also be modified as shown is the following snippet:

1 | for i in range(nb_epochs): |

The larger the batch size, the more stable the convergence, and we can also efficiently compute batch parameter updates using libraries such as pytorch, tensorflow, etc.

Implementation

All of the algorithms described above can be implemented in python.

Inspired by the pytorch notation, we, first defined an interface called Optimizer, which defines two methods, step() and zero_grad(). The former is used to update the parameters and the latter is used to zero the gradients.

1 | class Optimizer(): |

We then define the SGD optimizer as follows:

1 | class SGD(Optimizer): |

Now we can instantiate it and then integrate in the pytorch routine to optimize the model parameters. Note that this is a simple implementation of the algorithm, there are more efficient implementations also for sparse gradients.

Adam

The previous algorithms use a static learning rate defined a priori, we can do better. We can think of adapting the learning rate based on the surface. For example, if we have a steepest descent, we would increase the learning rate, and if we are reaching a saddle point, we might decrease the learning rate instead. This is the basic idea behind the family of algorithms that extend the basic GD algorithm, one of which is Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam).

This algorithm computes an adaptive learning rate for each parameter based on the average first moment, also makes use of the average of the second moments of the gradients.

More in details, this algorithm calculates the exponential moving average of gradients and square gradients. And the parameters $\beta_1$ and $\beta_2$ are used to control the decay rates of these moving averages. We can decompose Adam as a combination of two gradient descent methods, Momentum, and RMSP (Root Mean Square Propagation).

First we compute the decaying averages of past gradients and also squared denoted respectively as $m_t$ and $v_t$ as follows:

$$\begin{align}

m_t &= \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) g_t \\

v_t &= \beta_2 v_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) g_t^2

\end{align}$$

where $g_t$ represents the gradient. We can see that $m_t$ corresponds to the estimation of the mean and $v_t$ the variance not centered (2nd moment).

Now we can update the parameters using the following equation:

$$

\theta_{t+1} = \theta_{t} - \dfrac{\eta}{\sqrt{\hat{v}_t} + \epsilon} \hat{m}_t

$$

Implementation

1 | class Adam(Optimizer): |

AdamW

The $L^2$ regularization is a classic method used to reduce overfitting. This method basically consists in adding the sum of squared parameters (weights) of the model to the loss function, multiplied by a given hyper-parameter $\lambda$ also called weight decay. We can formalize the $L^2$ regularization as follows:

$$

\tilde J(\theta; x, y) = J(\theta; x, y) + \frac \lambda 2 \sum_i \theta_i^2

$$

Instead of modifying the loss function, we could instead simply modify the update equation to also subtract a portion of the paramater when updating it using a tecnique called weight decay. The update function would be:

$$

\theta = \theta - \eta \cdot \nabla_\theta J(\theta; x, y) - \eta \lambda \theta

$$

So, we have two methods that we could use to prevent overfitting, which one is the best? Luckily, Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter answer this question suggesting in their article that we should prefer the weight decay with Adam (hence the name AdamW), instead of the $L^2$ regularization.

Implementation

The implementation is straightforward, we only need to modify the step() method of the Adam optimizer adding the weight decay equation in line 24.

1 | class AdamW(Optimizer): |

Experiments

In this section we test the implemented algorithms on a classical quadratic convex loss function $f(x) = x^2$, so we have only one minimum with a cool descent.

Next, we choose a random starting point and then run the SGD, Adam, and AdamW algorithms on this loss surface, using the same learning rate. The results are shown in the following figure

We can clearly see that Adam and AdamW, using the same parameters, choose the same path behaving in the same way, while SGD takes a different path that also stops far away from the local minimum with respect to the other algorithms. This highlights the advantage of adapting the learning rate instead of using a fixed learning rate.

In the following figure, we show how Adam outperform SGD on reaching the minima

Conclusions & Further Readings

We have seen how the gradient descent can be used as a function optimizer. There are many optimizers in the wild, which one is better? There isn’t a unique answer. Some algorithms work better than others. As a rule of thumb, if you have sparse data, is preferable to use optimizers with an adaptive learning rate. SGD, generally, also performs well, but can be slow in certain scenarios. Selecting an appropriate learning rate, denoted as $\eta$, poses challenges: opting for a high value might lead to overshooting and missing the minima, whereas a lower value necessitates numerous steps to reach the minima. To tackle this issue, a methodology proposed in fastai, detailed in this article, can be employed. Similarly, for effectively determining other hyperparameters, the 1cycle policy presents a valuable approach.

We have only scratched the surface of the gradient descent algorithms. Numerous other variants exist, including RMSprop, AMSGrad, Adadelta, and more. It’s important to acknowledge that gradient descent isn’t always the optimal optimization algorithm. Alternatives, such as the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions or Newton’s method, can offer greater efficiency and stability in certain cases.

References

Gradient Descent explained

https://captwake.github.io/Machine-Learning/GradientDescent-Explained/